Decolonising Philanthropy

In an age of collapsing funding and existential threats, we must act together to reimagine a better future for the sector.

Introduction

Peace Direct has spent years delving into the systemic problems plaguing the wider humanitarian, development and peacebuilding sectors. Our research, including the landmark report Time to Decolonise Aid, spotlighted the extent of systematic racism and neocolonialism left unaddressed by power-holders across the entire international cooperation system. Our latest research findings, outlined here, demonstrate the prevalence of similar issues affecting global philanthropy.

In this guide, we outline the problems with current philanthropic practices, as identified by consultation participants, and share their recommendations for change. This is a tool to support philanthropists to work in solidarity with local actors to transform our sector together.

Methodology

These findings are based on an online consultation held in 2023 on Platform4Dialogue (P4D), as well as online focus group discussions and interviews. Questions revolved around the values and purpose of philanthropy, the discriminatory beliefs and assumptions underpinning it, and which areas to prioritise to build a new, decolonised model of philanthropy.

Overall, 197 participants, spanning 6 continents and 51 countries, participated in this exercise. Over 140 participants were locally based practitioners working with grassroots organisations, 17 participants were from 11 different foundations and funders, with the remainder from intermediary INGOs.

All quotes in this guide are from the aforementioned consultations. Participants gave their consent to the publication of these quotes. Some quotes were translated or modified for clarity and length. We are deeply grateful to all those who shared their insights, stories and expert analysis.

Findings

“There is no chance of decolonising if people are not prepared to step into the space of acknowledging their privilege and power, and it starts from inviting everybody to get to that uncomfortable space and stay there. […] And this is a conversation between the philanthropist and the local partners, it’s not a separate conversation, it’s both of us in the same room.”

Vuyiseka Dubula – Lead, African Advocacy and Partnerships, Stephen Lewis Foundation

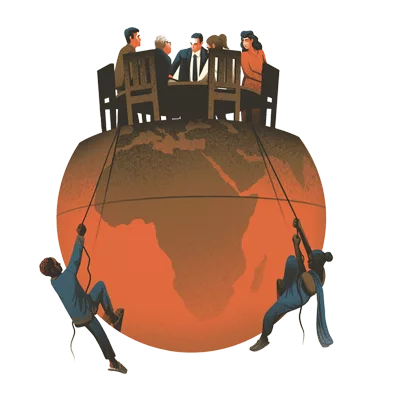

The wealth of philanthropic foundations and trusts was often built from extractive and exploitative practices. While some of this wealth has made positive contributions across the world, systemic racism, neocolonialism and White Supremacy are being upheld by the current philanthropic sector.

The problems of philanthropy

When we asked participants what aspects of global philanthropy reproduce neocolonialism and White Supremacy, they provided personal accounts of the main problematic practices and mechanisms that are perpetrated in different ways, consciously or unconsciously, both by Global North and Global South actors. Please hover over the flip cards below to explore each thematic issue and read associated comments from the consultation.

1

A sense of mistrust in Global South partners, manifested in the burden of excessive compliance…

2

…and only placed on the recipient.

3

A risk-averse attitude, which is widespread and often becomes controlling.

4

A lack of meaningful consultation of local communities and the imposition of Global North priorities.

5

A habit of ignoring local actors who are harder to reach, for example at the grassroots level.

6

A tendency to transplant mechanisms, structures and ways of working typical of the Global North…

7

…and the expectation that the Global South will conform to the requirements set by the Global North.

8

and to see projects as easy short-term solutions to what are in fact long-term, systemic issues that need long-term investment.

Why do these problems exist? Participants in the consultation argued that there are several harmful attitudes and beliefs, emulating a neocolonial and oppressive model of philanthropy, which are contributing to the above problems. These attitudes include:

1

philanthropists being ego-driven and self-centred…

“I think a large sense of ‘ego’ is predominant in international philanthropy. By this, I mean that some philanthropists put their definition of impact before that of the communities they are funding. It would be good to approach giving with a greater sense of humility; allowing recipients of funding to make decisions about the most meaningful use of the money, even when this is at odds with our own opinion.”

Sabina Basi – Director of Funding, Communications & Transformative Partnerships, ADD International

2

…and/or being rooted in White Saviourism.

“I think Teju Cole’s (2012) concept of the White Savior Industrial Complex is apt when it comes to thinking about some of the underpinnings of international philanthropy writ large. He wrote, ‘The white saviour supports brutal policies in the morning, charities in the afternoon, and receives awards in the evening’.”

Jasmine Linabary – University of Arizona

3

Dependence on philanthropic wealth from the Global North – perhaps by design – which also leads to the internalisation of oppression…

“It is complex to exit the international philanthropic system, even if you are in the ‘Global South’, since the subsistence of your organisation, movement, initiative and cause depend on it to a large extent. So, in the end our complacent attitude towards the international system stimulates the system to continue operating in the same way. I also consider that to some extent, as local actor, I have also replicated through my organisation these patterns and ways of thinking through the development of programmes.”

Luis Alvarado Bruzual – Co-creator, Peace Starts Here

4

…and complacency, on the part of both local organisations and philanthropists, to address any challenges.

“Most so-called philanthropists are people of interest with a well-defined agenda. They are interested in their own visibility and the reality of the purported ‘beneficiary’ communities is not their priority. […] Strings attached to alleged philanthropy is a known fact […], but what is even more worrying is the complacency of local elites who connive with these neocolonialist agents to exploit the local population.”

Nicoline Newnushi Tumasang Wazeh – Pathways for Women’s Empowerment and Development/Integrated Agricultural Training Center (PaWED-IATC)

Philanthropists are not blind to these issues, as many of them who participated in our consultation noted:

1

a longstanding neocolonial tendency to see Western/Global North knowledge as superior to local and Indigenous knowledge from the Global South.

“you still see instances of superiority feelings, the type of ‘I know best’ than local partners/actors. […] Very often we overlook that the capacity that local partners have is way more contextually useful, both in terms of their knowledge and networks. We’re not acknowledging that enough, it keeps our superiority feeling alive and their inferiority feeling as well.”

Floor Schuiling – Team Lead, Programmes and Partnerships, Mensen met een Missie

2

a lack of diversity at the board/trustee level which can, even inadvertently, lead to uninformed decisions that fail to consider the different lived experiences and needs of recipients and their communities…

“even with the right motivations, there’s a lot of decisions and discussions made for people [ie, partners], when it should be done with them. I can’t recall any situation where there’s a really discriminatory assumption done on anyone (at least not knowingly). The table was basically not big/diverse enough!”

Stefan Witthuhn – Senior Manager Grant Management, Finance and Administration, Robert Bosch Stiftung

3

…hence undermining the power and ownership of communities as the primary decision-makers.

“The primary accountability of community-led organisations needs to be to their communities […] to the people that they exist to serve and that make up their organisation. And if a philanthropist or other [funder] is getting in the way of that accountability, then you’re undermining the work that you’re doing.”

Healy Thompson

Solutions as proposed by participants

We also invited participants to share ideas about how to decolonise philanthropy. Recognising that the responsibility for decolonisation largely falls on philanthropic actors, as the main power-holders, key practical suggestions are:

Trust local partners to determine their own priorities, ways of working and objectives. In order to do this, structure grants around trust-based principles that can be established jointly with local partners and revised/evaluated continuously to allow flexibility to make mistakes, learn and improve.

Acknowledge, value and learn from the lived experiences and knowledge systems of local partner and their communities, using non-extractive practices that prioritise and fairly compensate their input.

Create a space for all actors to communicate openly, sharing their whole selves, and allowing themselves and others the time and conditions needed to be vulnerable.

Give generously and relinquish control over how philanthropic money is spent, and trust that local partners will have their own ways of accountability.

Recommendation 1

Recognise that global philanthropy is rooted in colonialism and exploitation, and accept full responsibility for the harm caused and/or perpetuated.

Eshban Kwesiga – Global Fund for Community Foundations

“The role of global philanthropy is to finally be brave to peel those layers and get into the conversations of what power looks like, how it has been exercised and maintained, and how the dynamics have affected people. Face the realities of our system […]. If a person/organisation is part of international philanthropy, they hold the (super)power to start this conversation. Yes, it’s uncomfortable but we need to.”

Olum Lornah Afoyomungu – Graduate Teaching Fellow, Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC), Makerere University

“After talking to communities and NGOs, we realised one of the aspects of the colonial legacy is what it does to your thinking. We sit here and think the communities or NGOs know what they want, but […] we realised no one had the answer. Coloniality is so deeply entrenched in us, that you can’t imagine another way. […] But we can be in the space and acknowledge the fact that we do not know different than this colonial structure. We cannot assume that, as actors, we know exactly how to change things.”

Recommendation 2

Challenge the values and beliefs behind philanthropic giving to understand how philanthropy can remedy its harm.

Tafadzwa Muropa – Economic Justice Activist and Development Practitioner

“International Philanthropy that benefitted from slavery and colonialism needs to take into account the needs of communities that have been affected by such structural injustices, and the form of reparation must not only seek to address the current generation but also ensure that future generations are not left in a disadvantaged situation.”

Eshban Kwesiga – Global Fund for Community Foundations

“There are many local organisations for whom accessing international money was always difficult, so they had to mobilise the local resources they had, and they built an alternative value and belief system outside what is familiar to global philanthropy. If global philanthropy seeks to challenge its own values/beliefs, it should start by studying the local organisations that have mobilized resources without it.”

Recommendation 3

“Trust generously.” (Arbie Baguios)

Vuyiseka Dubula – Lead, African Advocacy and Partnerships, Stephen Lewis Foundation

“We are asking that there’s a diversity of ways in which we can be accountable. […] Build on the already existing systems. It’s not that […] people should be given money and therefore do as they wish. We [i.e. philanthropy] trust that they will do as they said, and we trust in their systems, and we have been in the conversation where we also can let go of our power and our privilege, because we are not always going to be important in the conversation just because we are giving.”

Madonna Ainembabazi – Philanthropy Program Lead, CivSource Africa

“Decolonised philanthropy looks like optimism – it adopts an optimistic perspective, using positive language that enables us to view Africa as a place brimming with possibilities, rather than simply a region overwhelmed by problems, and avoiding the use of ‘problem statements and problem analyses.’ […] Decolonised philanthropy is dignifying and eliminates the shame and stigma associated with ‘begging’ for aid or fundraising. It also reduces the anxiety associated with micromanagement and eliminates the need to demonstrate one’s competence to every other [funder].”

Recommendation 4

Encourage open communications, authenticity and vulnerability.

Amjad Saleem – Peacebuilding Pracademic

“We need to approach this with humility, to actively listen to people, to understand what their needs are, what solutions they have to local problems and where we can actively partner with them providing not only grants, but also other support as necessary. Philanthropists should not assume that they come with the answers or that their money will provide the solutions […]. Ensure that we don’t start off with the premise that everyone is bad and out to rip you off but find ways of being inclusive and accessible for the funds.”

Shanthuru Premkumar – Program Advisor, Greenpeace

“Spend more time listening to needs and not rush into helping. Figuring out ways to build trust with communities, so it does not come as a saviour complex.”

Recommendation 5

Acknowledge, value and learn from the lived experiences and knowledge systems of grant partners and their communities.

Zack Gaya – CSO Network, Kisumu, Kenya

“To realise a decolonised philanthropy, I would prioritise listening that acknowledges that the people in places of need possess the perspective and wisdom needed to fix the issue. It calls for patient listening, taking the counselling diagnostic approach to help the people get to the root of the problem, exploring with them how it can be transformed, and then agreeing on the interventions to be prioritised. This process empowers the communities and puts them in the driving seat of resolving their issues.”

Rayana Rassool – Development Practitioner

“With less emphasis on parachuting people in from a Global North context, but to equally embrace skills and qualifications from the Global South. This means that qualifications from universities in the Global South need to be equally valued as well.”

Recommendation 6

Decentre philanthropic actors from decision-making positions in favour of people with intimate, authentic knowledge.

Matilda Maseno – Social Impact Consultant, Tangaza University

“A decolonised philanthropy is one that ensures that communities participate in curating their own solutions and eventually take charge of providing their own solutions. To achieve this, philanthropy needs to prioritise: investment in local leadership and co-design programmes with the communities; encourage and fund collaboration rather than competition; award unrestricted grants while facilitating capacity building for grantees on trust and accountability.”

Recommendation 7

Share challenges and reservations honestly.

Luis Alvarado Bruzual – Co-creator, Peace Starts Here

“I believe that the creation of more direct and horizontal communication channels between local actors and international philanthropic organisations is urgent in order to build mutual trust between both actors. I believe that trust building is vital in this process.”

Efe Omordia – Advocacy Strategist/Content Creator

“This mindset of seeing funders as saviours should stop. If recipients are not comfortable with the terms, they should not accept such help as it further dehumanises them. As tempting as it is to accept any help, the relief in the long-term may be too costly.”

Recommendation 8

Invest directly in diverse communities and movements, especially those that are most marginalised and under-resourced.

Arbie Baguios

“You don’t just give to Global South organisations that look like or sound like organisations in the Global North. There are mutual aid groups or self-help groups, there are indigenous entities or groups, tribal-based groups, faith-based groups. So really thinking about the diversity of Global South actors and not imposing a monoculture in terms of aid, but really approaching the polyculture of Global South actors and the solutions available in the Global South.”

Vuyiseka Dubula – Lead, African Advocacy and Partnerships, Stephen Lewis Foundation

“[Philanthropic funding] can be used to support marginalised groups that ordinarily the state is unable to fund, because of many reasons; laws that criminalise that particular community or population. Philanthropy has a role to come in there. Obviously, they must come in there very differently – flexible funding, long-term funding, generous funding, trusting funding.”

Recommendation 9

Identify the best ways to redistribute wealth and power to historically oppressed communities.

Michael Kourabas – Director of Partner Support & Grantmaking, UUSC

“Doing more than just writing cheques – showing up for our movements in the ways they most need, using our power and privilege to advance their advocacy goals, providing meaningful access to decision-making spaces, etc.”

Tafadzwa Muropa – Economic Justice Activist and Development Practitioner

“[Philanthropy] must recognise the importance of indigenous knowledge within the philanthropy sector, including acknowledging that local communities have the capacity to document their experiences and they have the right to safeguard their knowledge.”

Recommendation 10

Insist on holding funders accountable to the needs and aspirations of communities and to their own commitments.

Anonymous

“Philanthropy doesn’t try to work as a business, thinking about ‘Return on Investment (ROI)’, but instead focuses on itself to ensure it is following stated ways of giving away its wealth – and evaluates itself about how well it does not meet the expectations of movement builders/community organisations/local people.”

Recommendation 11

Give generously and surrender control over resources.

Carolin Gomulia – Director, The Workroom

“Everyone should be asking the question at all times – are we doing the best thing to solve the problem at hand? […] What do we need to do so that our money and resources are not needed anymore?”

Maria Kisumbi

“Philanthropy 2.0 would be about how communities come together to provide solutions/answers, mobilise resources. Philanthropy built on existing systems of community philanthropy. ‘It takes a village’.”

Change is possible.

For some, these changes may seem daunting. But our sector has already proven that change is possible. Three of Peace Direct’s most flexible funders have previously shared their efforts to improve their approaches – take inspiration from them:

Changing may not be easy, but this is not a challenge you can ignore.

Conclusion

Decolonising philanthropy means listening to local voices and reckoning with the past. It requires boldness, patience, and commitment to challenge and transform traditional power structures, dynamics, relationships, narratives, and practices. In the face of systemic threats, the sector has demonstrated its capacity to change and adapt. This moment is no different.

To create a better sector, we must address the unequal distribution of resources, extractive relationships with local partners, accountability gaps, and the imposition of Western agendas and values.

This is a call to question, reevaluate and transform the dominant, oppressive and neocolonial narratives that keep resources and power from local communities and in the hands of the Global North.

Many philanthropic actors are already on this journey, questioning their practices and actively promoting change. For true effectiveness, decolonising philanthropy requires solidarity among us all, room for uncertainty and continuous learning.

While the ideas, examples and recommendations shared here are non-exhaustive, we hope they can provide a foundation for action. By reallocating resources and decision-making power to those who have been most affected by inequality, injustice and oppression, philanthropic organisations can contribute to a transformation of our sector, and a more altruistic and just future.

If you’re keen to learn more about this work get in touch with us at info@peacedirect.org. And take a look at the resources below.

This research would not have been possible without the Decolonising Wealth Project. Learn more about their work here: https://decolonizingwealth.com/.

Discover practical tips from Peace Direct’s previous research in this extract from Transforming Partnerships in International Cooperation, created specifically for philanthropists and funders to complement Decolonising Philanthropy: https://www.peacedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Peace-Direct-Transforming-Partnerships-philanthropists-and-funders-extract.pdf. Source: Peace Direct, Transforming Partnerships in International Cooperation (2023).

Further resources:

- Arbie Baguios (2020), ‘The Aid Re-Imagined Model: Working paper – October 2020’, Aid Re-imagined (October 2020). Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/593eb9e7b8a79bc4102fd8aa/t/5fa1b444ef4f64607a0d0267/1604432966501/Aid+Re-imagined+mode+working+paper_Oct+2020%5B17741%5D.pdf.

- Exponent Philanthropy, ‘Actionable Ways To Add Diversity to Your Foundation Board and Staff’ (19 August 2022). Available at: https://www.exponentphilanthropy.org/blog/actionable-ways-to-add-diversity-to-your-foundation-board-and-staff.

- Geo Funders, What Does It Take to Spend Down Successfully? (29 July 2015). Available at: https://www.geofunders.org/resources/what-does-it-take-to-spend-down-successfully.

- Peace Direct, Time to Decolonise Aid (May 2021). Available at: https://www.peacedirect.org/publications/timetodecoloniseaid/.

- Peace Direct, Transforming Partnerships in International Cooperation (2023). Available at: https://www.peacedirect.org/transforming-partnerships/.

- Edgar Villanueva, ‘7 Steps to Healing’, Decolonizing Wealth (2018). Available at: https://decolonizingwealth.com/7-steps-to-healing/.

- Vodafone Foundation, Barriers to African Civil Society: Building the Sector’s Capacity and Potential to Scale Up, Vodafone Foundation/ClearViewResearch/Safaricom (2021). Available at: https://www.raceandphilanthropy.com/research.

- WINGS, What makes a strong ecosystem of support to philanthropy? (2018). Available at: https://wings.issuelab.org/resource/what-makes-a-strong-ecosystem-of-support-to-philanthropy.html.